What Is a Surety Bond for Security Companies?

Security companies live in a trust economy. Clients let you into sensitive spaces, regulators license you to operate near public safety, and your guards carry authority that affects real people. A surety bond sits quietly in the background of that trust, but it affects whether you win contracts, secure a license, or keep your doors open after a mistake. If you run or plan to launch a guard service, patrol firm, alarm installer, or investigations agency, it pays to understand how these bonds work, where they bite, and how to manage them like a professional.

The core idea, without the jargon

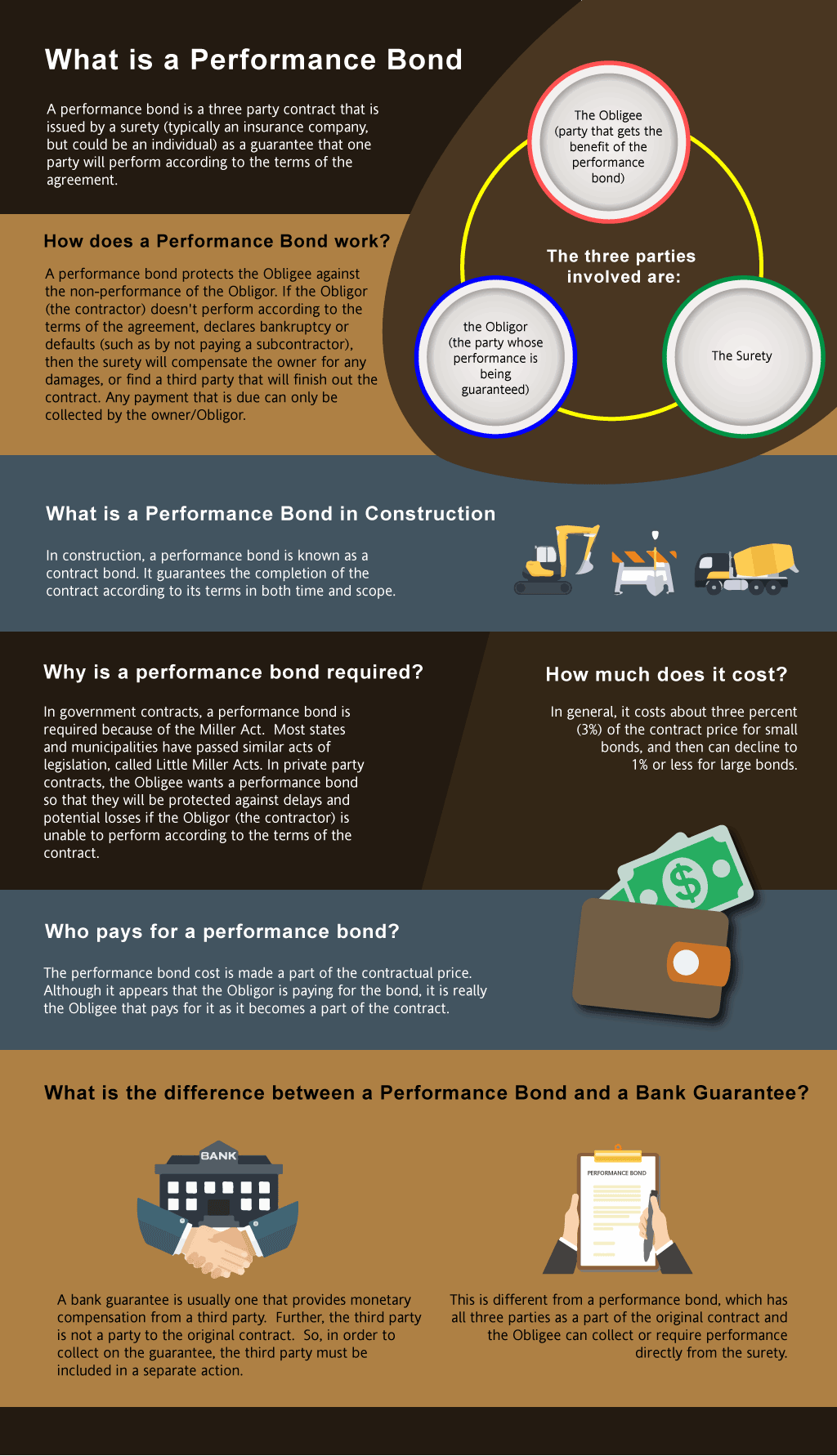

Think of a surety bond as a three-way agreement that guarantees you will follow the law and fulfill certain obligations. A security company, called the principal, buys the bond. The state licensing board or the client, called the obligee, requires it. A third party, the surety company, underwrites it. If the security company violates the law or the terms tied to the bond and causes a financial loss, the harmed party can file a claim against the bond. The surety investigates. If the claim is valid, the surety pays up to the bond’s limit. Then the surety turns around and seeks reimbursement from the principal.

That last part surprises newcomers. A surety bond is not insurance for the principal. It protects the obligee and the public. The principal ultimately bears the loss. This difference shapes how underwriters evaluate you, how claims get resolved, and how you should manage risk.

Where surety bonds show up in the security industry

Security firms encounter several flavors of bonds. The Swiftbonds names vary by state and by contract, but the patterns are consistent.

Licensing bonds. Most states require a bond as part of licensing for private patrol operators, security guard companies, alarm companies, and investigators. The bond amount might be 5,000, 10,000, 25,000, sometimes higher in large jurisdictions. The intent is simple: if you break a licensing law or fail to pay required wages or fees, injured parties can seek payment from the bond.

Contract performance bonds. Some clients, especially public entities or hospitals and universities, may ask for a performance bond and sometimes a payment bond on top of the license bond. A performance bond guarantees you will deliver guard services as promised in your contract. If you walk off the job or fail to meet minimum staffing hours and the client incurs costs rebidding the work, they can call the bond.

Employee dishonesty or business service bonds. These protect clients if your employee steals from them. Unlike licensing and performance bonds, many of these are sold as fidelity bonds, a cousin of surety. Some clients accept an employee dishonesty endorsement in your insurance program in place of a separate bond, but others specifically request a business service bond to cover theft by your staff at their premises.

Alarm or low-voltage contractor bonds. If you design, install, or monitor alarms or camera systems, local jurisdictions may require a separate bond tied to building codes and permit rules. Claims often arise from code violations, unpermitted work, or failure to pay permit fees.

Specialty bonds. Court appeal bonds for disputes, utility deposit bonds for monitoring centers, or wage-and-welfare bonds if you operate under certain union agreements. They come up less often, but when they do, lead time matters.

Across these categories the theme is consistent: the bond backs a promise. Break the promise, pay the bill.

How underwriters look at a security firm

Surety underwriters behave more like bankers than insurers. They want to know if you can keep your promises and, if something goes wrong, whether you can reimburse them. For a start-up guard company, the review might be light, especially for a small license bond. For larger performance bonds or cumulative bond programs, expect a deeper dive.

They focus on three areas. First, character. They look for unpaid tax liens, prior bond claims, criminal convictions related to fraud or violence, and licensing violations. Second, capacity. This means operational capability. Can you staff the posts, supervise the shifts, and manage scheduling without constant overtime? Have you fulfilled contracts of similar size? Third, capital. They evaluate financial statements, working capital, cash flow, and bank lines. They want a cushion that absorbs payroll swings, late client payments, and claim costs.

Most personal credit scores above the mid-600s open the door for routine bond approvals at good rates. Premium for small license bonds often ranges from 1 percent to 3 percent of the bond amount per year, sometimes a flat fee for low limits. Performance bond rates vary with risk, size, and duration, and can be lower per thousand for well-qualified firms. Bad credit does not shut you out, but it raises premiums and can trigger requirements like collateral or a co-signer.

What the bond actually covers, and what it does not

Bonds respond to specific obligations. If a state’s private security act says you must maintain payroll records, pay minimum wages, avoid false advertising, and notify the board of material changes, the license bond often points back to those statutes. A claim based on a guard’s rudeness does not usually reach the bond. A claim based on unpaid wages or illegal subcontracting might.

Performance bonds follow the contract. If you promised two armed supervisors on swing shift and deliver only one, that is a performance issue. If you deliver the staff but an employee injures a bystander, that is a liability claim for your insurance, not the bond. When clients blur the lines, the surety will push back and compare the allegation against the bond’s language.

Fidelity or dishonesty bonds address theft by your employees from your client. They do not cover your own internal theft, unless your policy includes first-party coverage. They do not cover accidental damage or professional errors.

A good rule of thumb: bonds secure duties; insurance covers accidents.

The claim process, step by step

No one wants to see the surety’s claims department on caller ID, but understanding the process makes a rough moment manageable.

A claimant files with the surety. For license bonds the claimant might be a consumer, an employee, or the state agency. For performance bonds it is the client. Documentation accompanies the claim: the contract, the statute violated, invoices, time sheets, or a narrative of events.

The surety investigates. This includes reaching out to you for your side, requesting documents, and comparing facts to the bond’s language. They are not your lawyer, although they do value a clear, credible response. Time matters here. Silence reads as weakness.

If the claim is valid, the surety pays up to the bond amount. Payment may go to the claimant directly or to the obligee for distribution. The surety then exercises its right to indemnity and seeks reimbursement from you. This can include the claim payment, legal costs, and investigation expenses.

For performance bonds there is an additional fork. If you default mid-contract, the surety can arrange completion in several ways: finance you to finish, find another contractor, or pay the penal sum and walk. The best outcome is almost always the first option, because it limits costs and protects your reputation.

Practical examples from the field

A guard firm in Texas lost a mid-sized municipal contract over missed posts and excessive call-offs during a holiday season. The city made a claim on the performance bond for the cost of emergency coverage with a different vendor. The surety validated the schedule gaps and paid a fraction of the total claimed amount after negotiating down the emergency rates and excluding hours that were outside the original scope.

A start-up patrol company in California faced a license bond claim from a former employee who alleged unpaid overtime and missed meal breaks. Wage claims fall squarely under the licensing statute there. The surety paid the award after a labor board ruling. The owner reimbursed the surety over six months and revamped scheduling rules to avoid repeat issues, including automated meal-break alerts.

An alarm installer in Florida had a low-voltage contractor bond. After an inspection flagged unpermitted wiring across three sites, the county filed against the bond to recover re-inspection and enforcement costs. The surety paid the fees, then billed the installer. The installer learned an old lesson: a day saved by skipping permits becomes a month lost in fines and remediation.

These are ordinary, not catastrophic, and they show the main triggers: staffing failures, wage law compliance, and code violations.

The bond amount and what it means for risk

A bond’s penal sum is the maximum the surety will pay on your behalf. For a 10,000 license bond, the worst-case check from the surety is 10,000, not counting legal costs you will also owe. For performance bonds, the penal sum usually equals the contract amount or a percentage of it. On an annual guard services contract worth 2 million, a 100 percent performance bond creates significant exposure.

The penal sum also affects underwriting scrutiny. License bonds at 10,000 or 25,000 often get automated approval. A first performance bond at 250,000 gets a human underwriter. Anything past seven figures gets a full workup with financials, resumes, job references, and maybe a meeting. Plan your growth with this in mind. It is easier to establish bonding capacity incrementally than to jump from unbonded to a multi-million bonded contract in a single bid cycle.

What is a surety bond, practically speaking, for your cash flow

Premiums are typically annual for license bonds and per-term for project bonds. Many sureties allow monthly pay for small bonds, but most expect annual pay upfront. If you cancel a license bond mid-term because you exit a state, you can usually secure a pro-rated refund once the obligee releases the bond.

Large performance bonds can require collateral if your financials are thin or the job stretches beyond a year. Collateral ties up liquidity and can slow hiring or equipment purchases. This is why seasoned operators maintain a line of credit and conservative cash reserves. The surety is more comfortable supporting you when you can demonstrate that you do not need their help.

Compliance traps that trigger claims

New owners often underestimate regulatory detail. Security work touches wage and hour laws, firearm rules, training mandates, background checks, and recordkeeping. Bond claims tend to cluster in a few areas.

Missed wage and break requirements. Guard posts run long. If supervisors ignore break logs or alter time records, a wage claim can land on your license bond, especially in states with strict private security statutes and aggressive labor enforcement.

Unlicensed activity. Running with an expired license, using unregistered guards, or advertising services beyond your license class can trigger administrative penalties and bond claims for restitution.

Failure to meet contract staffing or supervision. For performance bonds, under-delivery is the most common default. If you sign up for 24/7 coverage at three posts, but do not field a reliable relief pool for sick days, the holes will show.

Code and permit issues for alarm work. Pull permits, pass inspections, and document. The paper trail protects you.

Unpaid vendors on bonded jobs. If the client required a payment bond, unpaid subcontractors or suppliers can claim. Even if you dispute their performance, keep documentation tight and respond quickly.

A professional approach treats compliance like operations: measured, trained, and audited.

How to buy the right bond, the right way

Security firms buy bonds from licensed insurance agents or surety brokers. Some carriers write directly. Work with someone who sees security firms regularly. They will know the standard bond forms used by your state board or your public-sector clients and can spot landmines in custom forms.

For a license bond, expect to provide your application, owner info, business address, years of experience, and sometimes personal credit authorization. Approval can be same day. For performance bonds, assemble a simple but complete package: the contract or RFP, your pricing breakdown, resumes of key managers, bank reference, and the last two to three years of financial statements and tax returns. If you are young but growing fast, add a one-page narrative describing staffing plan, supervision ratio, wage structure, overtime policy, and training. Underwriters want to see how you will keep the posts filled without burning out your team or your balance sheet.

If the client’s bond form looks extreme, ask for revisions. Key red flags include unlimited liability beyond the penal sum, waiver of defenses, or vague performance standards. Public entities are often firm, but they do accept standard industry forms when asked early.

Managing the bond program as you scale

Bonding capacity grows with credibility. The simplest way to build it is to perform well on smaller bonded contracts, keep financial statements clean and timely, and talk to your surety before you bid a stretch job. An underwriter who hears from you quarterly will stretch farther than one who sees you only when you need a rushed approval.

Internal controls help. A few practices pay off quickly.

Real-time scheduling and absence management, including backup rosters and minimum notice policies Supervisor-to-guard ratios that reflect site risk, not just headcount Documented post orders, incident reporting, and training logs Monthly reconciliation of hours billed against hours paid to catch wage risks A contingency plan for sudden client scope increases, weather events, and labor shortages

These habits reduce claims and give you hard evidence when a claimant exaggerates.

Insurance versus bonds, and why both matter

Clients and new administrators sometimes mix up insurance certificates and bonds. You need both. General liability covers bodily injury and property damage accidents. Professional liability or errors and omissions might apply for consulting or policy design work. Workers compensation covers employee injuries. Auto covers patrol cars. These respond to negligence and accidents.

Bonds address your obligations to deliver service as promised and to follow the law. They are not interchangeable. A client who receives your insurance certificate is not protected against your default unless a bond backs the contract. A state licensing board will not accept insurance in place of a statutory bond.

One more nuance: many clients ask for additional insured status on insurance policies. They cannot be named as an additional insured on a bond. The bond name must match the obligee’s requirement and your legal entity name, and that is it.

The human side of claims and defaults

When a company defaults on a bonded contract, fallout lands on people. Guards lose hours, clients scramble, reputations suffer. I have seen sureties quietly finance a struggling operator through the last three months of a contract to avoid chaos. They will ask for collateral, daily reporting, and a lean plan. If you find yourself near that ledge, call your broker and surety early. The earlier the conversation, the more tools they can use. Silence narrows options to termination and payment, which costs more, hurts longer, and leaves fewer paths back.

On wage and hour matters, humility and speed help. If a labor board has already ruled against you and the surety paid, set up a repayment plan quickly. Pair it with a concrete fix: new scheduling software with break alerts, supervisor training, or a policy change to eliminate off-the-clock work. Show your surety you learn and adapt.

Cost, timing, and the seasonal rhythm of bonds

License renewals cluster around calendar year-ends in many states, and performance bond requests spike during public bidding seasons. Lead time improves pricing and keeps you from paying rush fees. For simple license bonds, two to three business days is safe. For performance bonds under half a million, a week is reasonable once your financial package is current. For seven figures and above, give it two to three weeks, especially if the bond form is nonstandard or if you are new to the surety.

Premium budgeting looks small for license bonds and material for large performance bonds. A 10,000 license bond at 2 percent runs 200 annually. A 1.5 million performance bond at 1 percent per year over a two-year term runs 30,000, often paid upfront. Build these numbers into your pricing. On public bids, your competitors already have.

Edge cases and special considerations

Joint ventures. If you team with another firm to bid a large campus contract, the surety may require a joint venture agreement and cross-indemnity. This binds each partner to the other’s performance. Negotiate the JV terms carefully, including who controls scheduling software, whose supervisors lead, and how disputes resolve.

Subcontracting. If you use subs to cover overflow, confirm licensing and insurance for each sub and ensure your contract allows it. Some obligees treat unapproved subcontracting as default under the performance bond.

Multi-state operations. Bond requirements change at state lines. A company expanding from Arizona into Nevada and California will face three different license bond amounts and forms, plus local jurisdiction demands. A national broker with a surety team helps you avoid last-minute scrambles.

Armed services. Contracts requiring armed guards draw more scrutiny. Underwriters look for training records, range qualifications, use-of-force policies, and incident logs. Demonstrate a clear escalation policy and supervision model.

Rapid growth. Doubling revenue off one big win feels great until payroll arrives before the client’s first check. Surety underwriters know this gap. Show a cash flow projection and a bank line sufficient to carry 30 to 60 days of payroll. It will mean the difference between approval and denial for performance bonds.

Making the bond work for you in sales

A clean bonding track record is a sales asset. Mention your bonding capacity and your claim history in proposals. Offer to have your surety provide a letter of bonding ability for larger bids, confirming that a reputable carrier stands behind you up https://penzu.com/public/341c72df1c7ea296 to a specified limit. It reassures procurement teams who have been burned before. Pair this with references that speak to schedule integrity and supervisor responsiveness. Procurement officers care less about glossy brochures than about whether you show up on time, every time.

A clear answer to the question

What is a surety bond for a security company? It is a financial guarantee to your regulator or client that you will follow the law and deliver the service you promised. It is underwritten against your character, capacity, and capital. It pays the injured party if you default, then you reimburse the surety. It is not insurance for your benefit, though it protects your ability to operate by satisfying legal and contractual requirements.

Handled well, a bond fades into the background while you serve clients. Misunderstood or neglected, it can become the most expensive line on your balance sheet. Treat it with the same diligence you apply to post orders and payroll. Build the right relationships with a knowledgeable broker and a surety that understands the security sector. Keep your financials clean, train your supervisors, and track your staffing promises as carefully as your hours. Do that, and the bond becomes what it should be: a quiet promise that backs the trust you ask others to place in you.

Quick starting checklist for owners

Verify your state’s license bond amount and form before filing an application Line up a surety broker who routinely works with security firms Document staffing plans, supervision ratios, and wage policies for underwriting Read client bond forms early and negotiate unrealistic terms Track hours billed versus hours paid monthly to prevent wage-related claims

Sprinkle in plenty of common sense and a little discipline, and the bond will support your growth rather than stand in your way. If someone on your team ever asks what is a surety bond, tell them it is the promise behind the uniform, written in dollars, enforced by a third party, and earned by how you run the business day to day.