Despite Propaganda Campaigns, Hungarians Have Not Become More Anti-EU or Sovereignty-Obsessed

Since 2023, Hungary has experienced a peculiar political situation where central propaganda has heavily relied on a concept that most voters cannot precisely define—sovereignty. This word even has its own "defense office," possessing powers typically associated with similar institutions in dark dictatorships.

But how do Hungarians actually relate to this unusual, foreign-origin term they've been forced to coexist with for quite some time? Zsófia Tomka sought to answer this question in her study titled "National Sovereignty, Sovereignism, and the European Union – Public Attitudes in Hungary, 1995–2023," published in the 2024 Social Report by TÁRKI.

At the outset, Tomka herself acknowledges the challenge of her task, aiming to avoid treating "national sovereignty as an objectively observable phenomenon or operationalized concept with easily measurable extents." Instead, her study primarily investigates Hungarians' opinions about the government's propaganda-driven definition of sovereignty:

"Power must be reclaimed from global actors—such as international organizations like the European Union or purely economic entities like global corporations—and nation-states must be strengthened. This idea is rooted in national sovereignty."

For her research, Tomka utilized data collected in Hungary by the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP). ISSP covers various topics, with national identity being particularly relevant to sovereignty-related questions and responses. Representative samples of Hungary’s population answered these questions in 1995, 2003, 2013, and 2023, especially focusing on attitudes toward the EU and sovereignty.

In ISSP surveys, respondents rate their agreement with statements on a scale from one to five, such as: "Hungary should limit the import of foreign goods to protect its economy" or "Hungary must comply with EU decisions even when disagreeing with them." Similar scales address questions about whether the EU should have significantly more, more, the same, less, or significantly less power compared to member states' governments.

As Tomka points out, before Hungary's 2003 referendum—where 84% chose EU accession, leading to membership the following year—there was practically unanimous political consensus on supporting European integration. However, this consensus has since eroded.

With the 2015 refugee crisis, the EU (or "Brussels") became an enemy in government propaganda, intensifying to the point that various European politicians became targets of hate campaigns through billboards and government rhetoric. It is particularly interesting, therefore, to explore how this dissolution of political consensus impacted Hungarians' views on sovereignty and European integration.

Based on responses, Tomka identifies four distinct groups within the Hungarian population:

- Sovereignists, who hold sovereignist positions in both political and economic issues.

- Economic sovereignists, who prioritize sovereignty in economic matters only.

- Political sovereignists, who prioritize political sovereignty matters only.

- Non-sovereignists, who have no sovereignist views in either domain.

Table 1. Distribution of groups formed on the basis of opinions about sovereignty in Hungary, 1995–2023 (%)

| 1995 | 2003 | 2013 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non‐sovereigntist | 17 | 13 | 15 | 23 |

| Economic sovereigntist | 66 | 67 | 64 | 52 |

| Political sovereigntist | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Sovereigntist | 15 | 17 | 17 | 20 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| (N) | (1000) | (1021) | (1007) | (985) |

Source: Own calculations based on the Hungarian data of the ISSP from 1995, 2003, 2013, and 2023. Data collection for the 2023 wave took place in January 2024.

Note: Comparability is limited by the fact that in 1995 only two economic‐sovereignty‐related questions were included in the questionnaire, as opposed to three in the later waves.

The proportions among these four groups have remained remarkably stable for nearly 30 years. The non-sovereignists slightly increased but still remain less than one-third of those holding some sovereignist views.

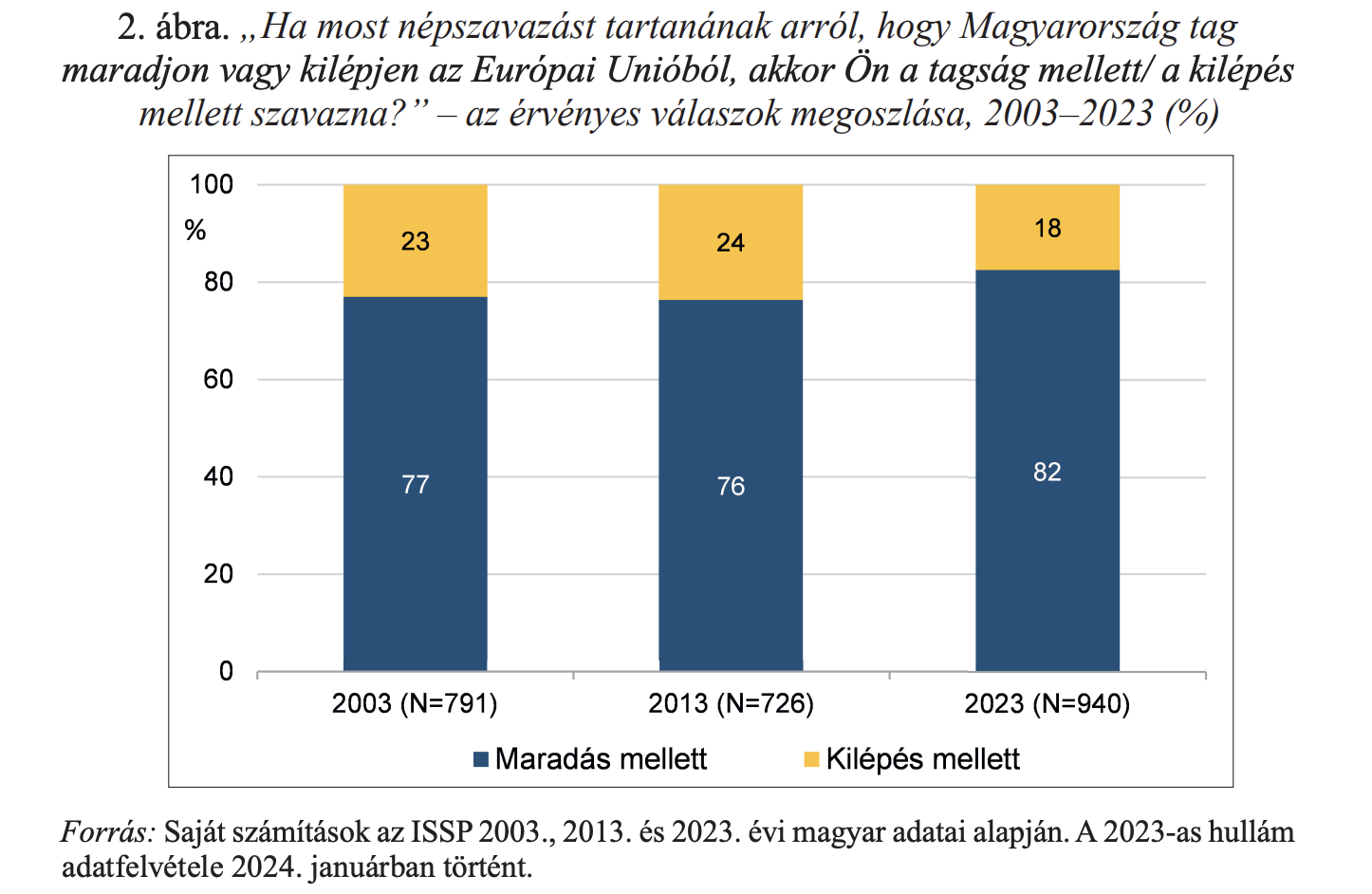

Nevertheless, this does not imply that the EU is unpopular in Hungary. ISSP figures, along with all similar surveys, clearly indicate Hungarians are fond of the EU. Twenty years after the accession referendum, nearly the same number support membership as initially.

Figure 2. "If a referendum were held now on whether Hungary should remain a member of the European Union or leave, would you vote to remain or to leave?" – distribution of valid responses, 2003–2023 (%)

- Blue: In favor of remaining

- Yellow: In favor of leaving

Source: Own calculations based on the Hungarian ISSP data from 2003, 2013, and 2023. Data for the 2023 wave were collected in January 2024.

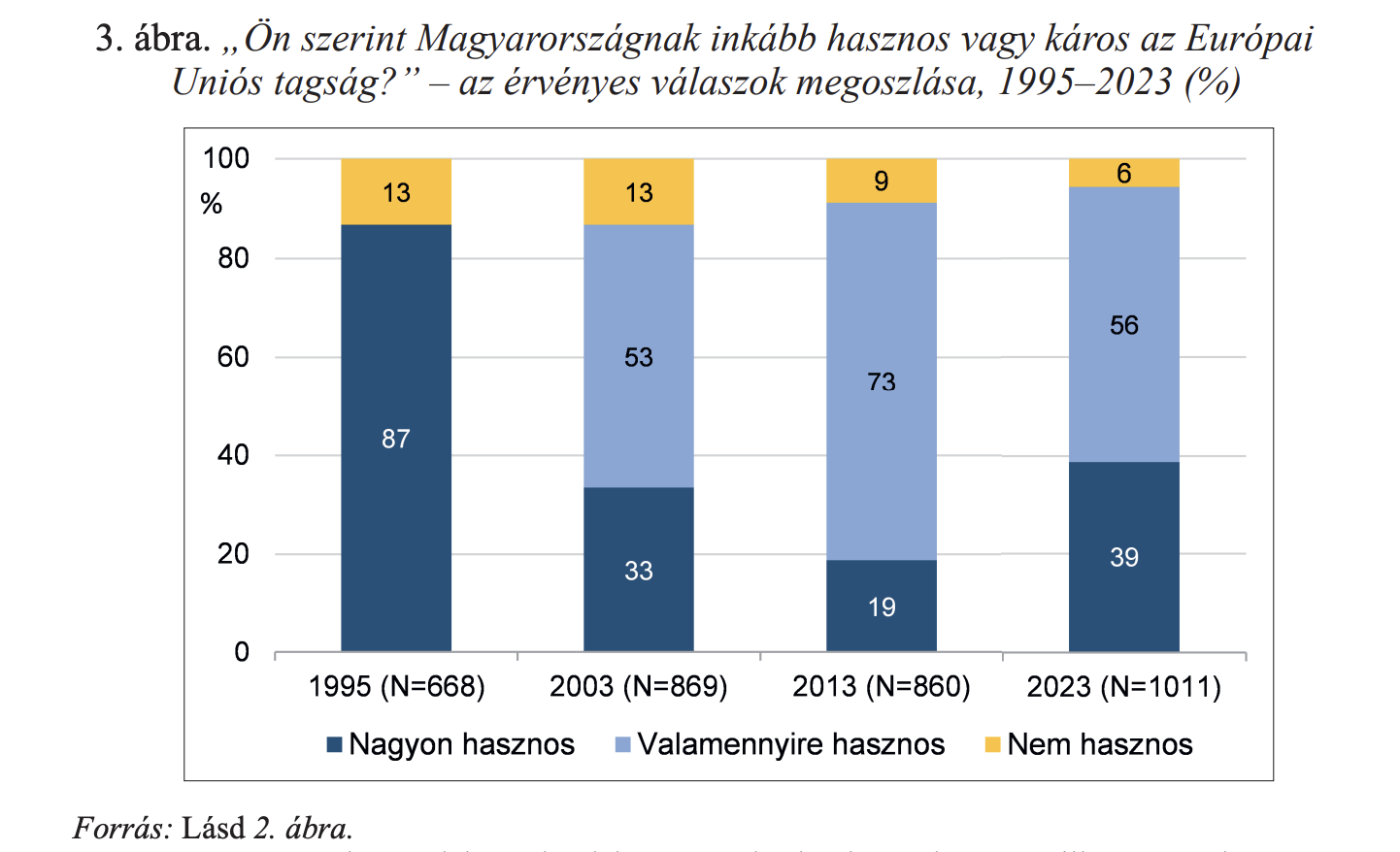

The situation is even clearer when examining how beneficial Hungarians find EU membership. Indeed, the number of Hungarians who believe membership is completely useless has halved, practically disappearing.

Figure 3. “In your opinion, is Hungary’s membership in the European Union more beneficial or more harmful?” – Distribution of valid responses, 1995–2023 (%)

- Dark blue: Very beneficial

- Light blue: Somewhat beneficial

- Yellow: Not beneficial

Source: See Figure 2.

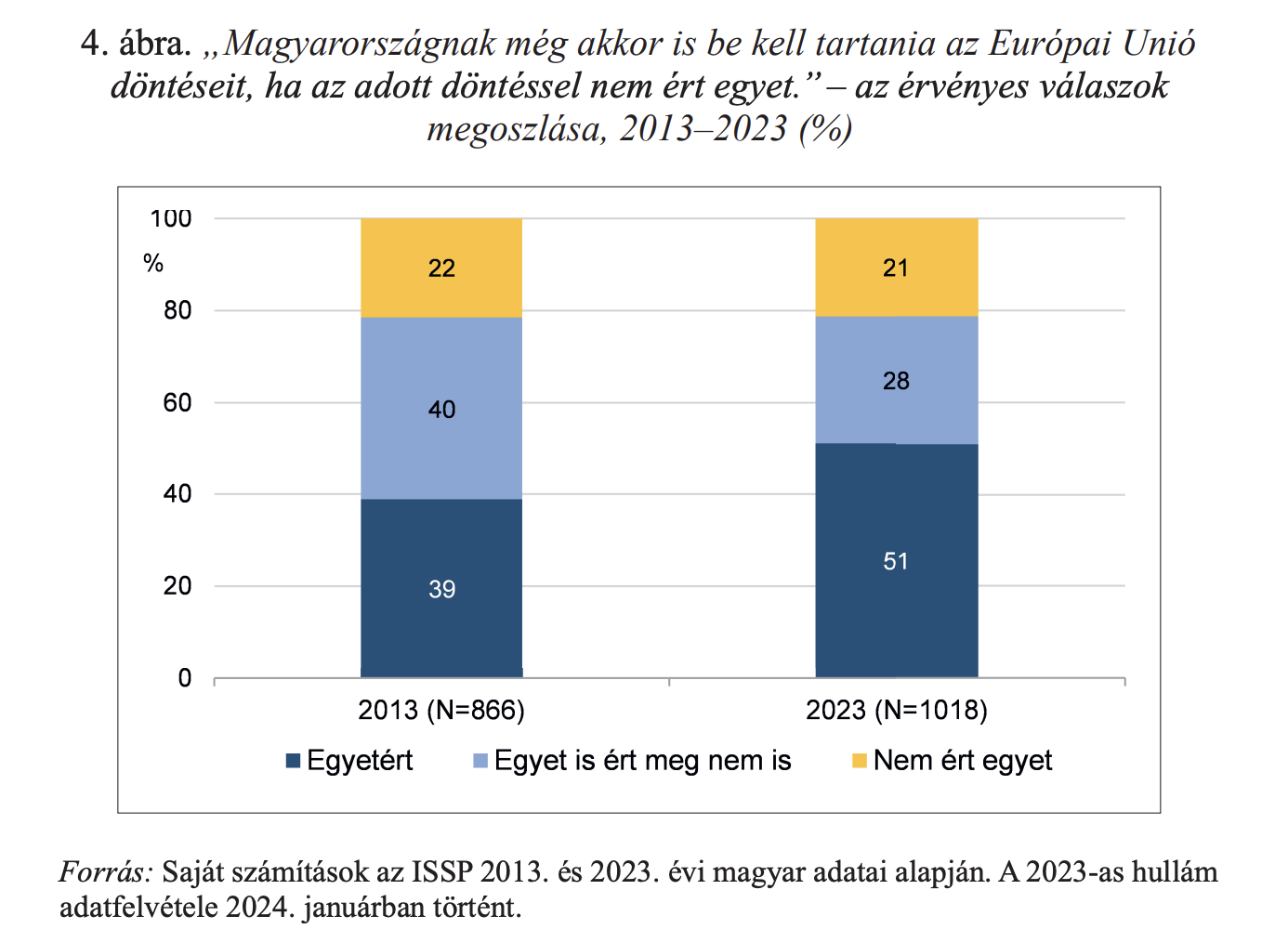

Perhaps the most striking finding from the research is the percentage of Hungarians agreeing that Hungary should comply with EU decisions even when disagreeing with them.

Figure 4. “Hungary must abide by the European Union’s decisions even if it disagrees with a particular decision.” – Distribution of valid responses, 2013–2023 (%)

- Dark Blue: Agree

- Light Blue: Somewhat agree and somewhat disagree

- Yellow: Disagree

Source: Own calculations based on the 2013 and 2023 Hungarian ISSP data. Data for the 2023 wave were collected in January 2024.

Although perhaps forgotten by many, Hungary held a referendum in 2016 on mandatory EU quotas for migrants. The referendum asked voters:

"Do you want the European Union to impose the mandatory settlement of non-Hungarian citizens in Hungary without Parliament’s consent?"

The referendum was invalid due to low turnout (below 50%), though more than 98% voted "no." ISSP figures, however, suggest that less leading question phrasing could yield different outcomes. A significant number of Hungarians believe the country should comply with EU decisions even when disagreeing. Moreover, despite ongoing anti-EU propaganda campaigns, those fully agreeing with compliance increased from 39% in 2013 to 51% in 2023.

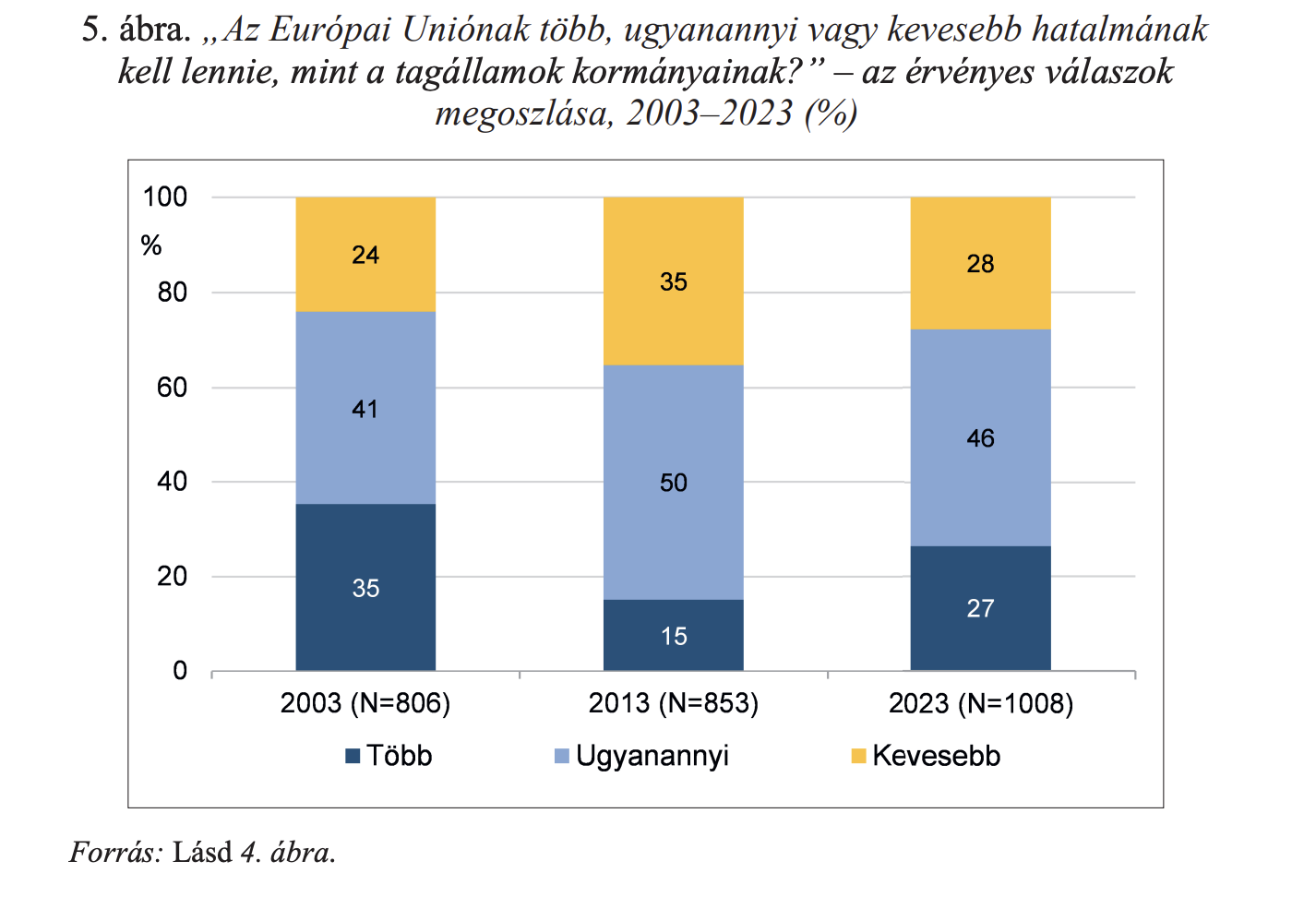

However, opinions are more mixed regarding whether Hungarians favor more or less power for the EU relative to member states' governments.

Figure 5. “Should the European Union have more, the same amount, or less power than the governments of its Member States?” – Distribution of valid answers, 2003–2023 (%)

- Dark Blue: More

- Light Blue: The same amount

- Yellow: Less

Source: See Figure 4.

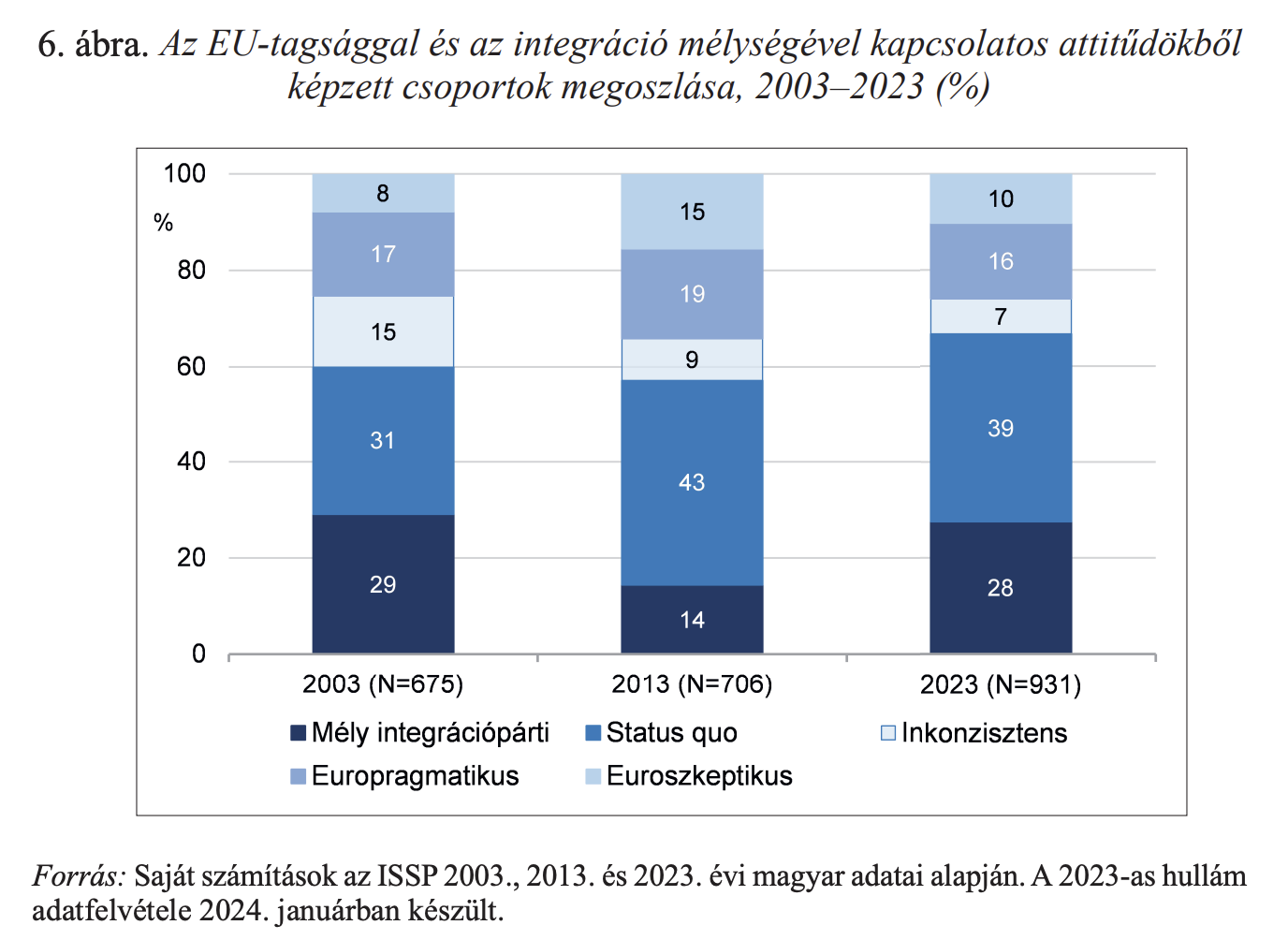

In 2023, there was a minimal increase in those wanting less EU power compared to national governments. Tomka categorizes Hungarians into five groups based on these views, attitudes towards EU membership, and the depth of European integration:

- Deep integration supporters, favoring EU membership and deeper integration.

- Status quo supporters, favoring membership with equal power between the EU and member states.

- Inconsistent respondents, who would vote to leave the EU yet grant it equal or greater powers.

- Euro-pragmatists, favoring EU membership but giving it less power than national governments.

- Eurosceptics, consistently anti-EU, supporting withdrawal and opposing EU power exceeding national governments'.

Figure 6. Distribution of groups formed on the basis of attitudes toward EU membership and the depth of integration, 2003–2023 (%)

Legend (from bottom to top in each bar):

- Dark Blue: Pro–Deep Integration

- Medium Blue: Europragmatic

- Light Blue: Status Quo

- Light Gray/Blue: Eurosceptic

- Top (Lightest): Inconsistent

Source: Own calculations based on the 2003, 2013, and 2023 Hungarian ISSP data. The 2023 wave was collected in January 2024.

Compared to 2003, the proportions in 2023 haven't significantly changed. If anything, there's been slight growth in those satisfied with current EU conditions or supporting deeper integration. Those favoring withdrawal or stronger positions against the EU are decreasing.

ISSP data also allow analysis of sovereignty and EU-related attitudes within specific social groups. Tomka highlights that these two topics increasingly intertwine. Starting from 2013, the data show that withdrawal advocates and Eurosceptics prioritize sovereignty more than deep integration supporters. By 2023, this correlation had intensified, particularly among people with lower education and rural residents. Tomka emphasizes that the data

"leave little doubt that questions of sovereignty are now connected to public perceptions of the EU."

Hungary’s party landscape changed significantly over twenty years, yet some constants, like Fidesz, remain. ISSP data illustrate how the proportion of sovereignists among party voters changed.

Figure 7. Changes in the distribution of “sovereignty groups” by party preference in Hungary, 2003–2023 (%)

Year Panels:

- 2003 (top panel): Fidesz, MSZP, SZDSZ, Other, Would not vote

- 2013 (middle panel): Fidesz–KDNP, MSZP, LMP, Jobbik, Did not vote

- 2023 (bottom panel): Fidesz–KDNP, Opposition alliance, Mi Hazánk (“Our Homeland”), Other, Did not vote

Vertical axis: Percentage of respondents (0–100%)

Stacked Categories (from bottom to top in each bar):

- Non-sovereigntist (darkest)

- Economic sovereigntist

- Political sovereigntist

- Sovereigntist (lightest)

(For example, in the 2023 Fidesz–KDNP column, 13% are Non-sovereigntist, 54% Economic sovereigntist, 4% Political sovereigntist, and 30% Sovereigntist, etc.)

Source: Own calculations based on Hungarian survey data from 2003, 2013, and 2023. Data for the 2023 wave were collected in January 2024.

Even among Fidesz voters, the proportion of non-sovereignists slightly increased over twenty years, yet the number fully committed to sovereignism nearly doubled. Conversely, among voters of broadly left-wing opposition parties, the proportion firmly opposed to sovereignism dramatically rose, approaching 50% by 2023.

It seems that nearly a decade of anti-EU agitation partially turned Fidesz voters against "Brussels," but also transformed opposition voters into even stronger advocates for European integration.